Current research on sustainable regions includes a study on the outcomes of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development's Sustainable Communities Initiative (SCI). For this study, planners in 74 regions around the country were surveyed on their experiences with SCI, which led to the creation of case studies on collaboration in the federal government and in SCI grantee regions to serve as examples and models. Ongoing research includes case studies on the work of cities, suburbs, regional government, and cross-sector collaborators on implementing regional sustainability plans.

Center for Community Innovation Research

The report begins with a brief review of previous research on barriers to identify the gaps in our knowledge. It then describes the context for ADUs in the three cities, including the policies each implemented to spur more construction. Next, the report turns to the survey methods and results. A conclusion suggests policy approaches to spur more ADU construction. Most prominent among them are eforts to make loans for ADU projects more accessible to more homeowners. This would be a difcult undertaking but one with a likely high payof. In addition, providing city-approved manuals detailing the regulatory, design, and project management processes for ADU projects for homeowners, coupled with technical assistance and promotional eforts would also likely help boost production.

The shortage of afordable housing in the Bay Area has precipitated the development of innovative housing solutions throughout the region. One of these solutions is the accessory dwelling unit (ADU), or second unit. Self-contained, smaller living units on the lot of a single-family home, second units are a well-suited infll strategy for low-density residential areas as they can be produced afordably and are already a common architectural form that neighbors are less likely to fnd objectionable. Second units are also fexible in their design: they can be attached to the primary house, such as an above-the-garage unit or a basement unit (attached ADU) or, as is more typical, an independent cottage or carriage house (detached ADU).

In 2003, the State of California passed Assembly Bill 1866, which required each city to have a ministerial process for approving second units. The State has continued to loosen regulations in order to facilitate ADU production, most recently through new laws (Senate Bill 1069, Assembly Bill 2299, and Assembly Bill 2406) reducing parking requirements and allowing junior accessory dwelling units.

San Mateo County Board of Supervisors recently updated its Second Unit Ordinance to encourage ADU construction, both to comply with State law as well as to streamline the production of ADUs as a strategy for relieving pressure in the county’s strained housing market. Funded by the San Mateo County Housing Innovation Fund, this study explores the possibility for greater ADU adoption throughout the County’s unincorporated areas. This report is based on a physical feasibility study, analysis of resident demographics, and an examination of the fnancial barriers to ADU adoption (based on interviews with fnancial experts and local residents). We present detailed fndings in three technical reports (available at http://communityinnovation.berkeley.edu): Technical Report #1: Estimating ADU Potential in Unincorporated San Mateo County; Technical Report #2: ADU Demographic Analysis in Unincorporated San Mateo County; and Technical Report #3, ADU Financing Issues in Unincorporated San Mateo County (including sample pro formas).

The following explores the potential for ADU construction in unincorporated San Mateo County. The report begins with an analysis of the physical feasibility of construction and then describes the potential market for ADUs. Following an analysis of fnancial barriers for diferent types of homeowners, a conclusion ofers policy recommendations.

California is at the cutting edge of the sustainability movement, not only because it has enacted laws that actively reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also because its pioneering environmental regulation, market innovation, and Left Coast politics show how to blend the "three Es" of sustainability—environment, economy, and equity. This grand experiment offers lessons about the “most just”path for cities and regions across the globe and provides a framework to deal with the new inequities created by the movement for more livable—and more expensive—cities, so that the best plans for sustainability may be designed to promote more equitable development as well.

This report presents three housing development scenarios for the state through 2030: (i) a business-as-usual “baseline,” (ii) a “medium” infill sce- nario, and (iii) an infill “target” scenario. All three scenarios assume that the state will build enough housing to meet projected population increases through 2030 as forecast by the state’s Department of Finance. They vary only in the loca- tion and housing types that would be built.

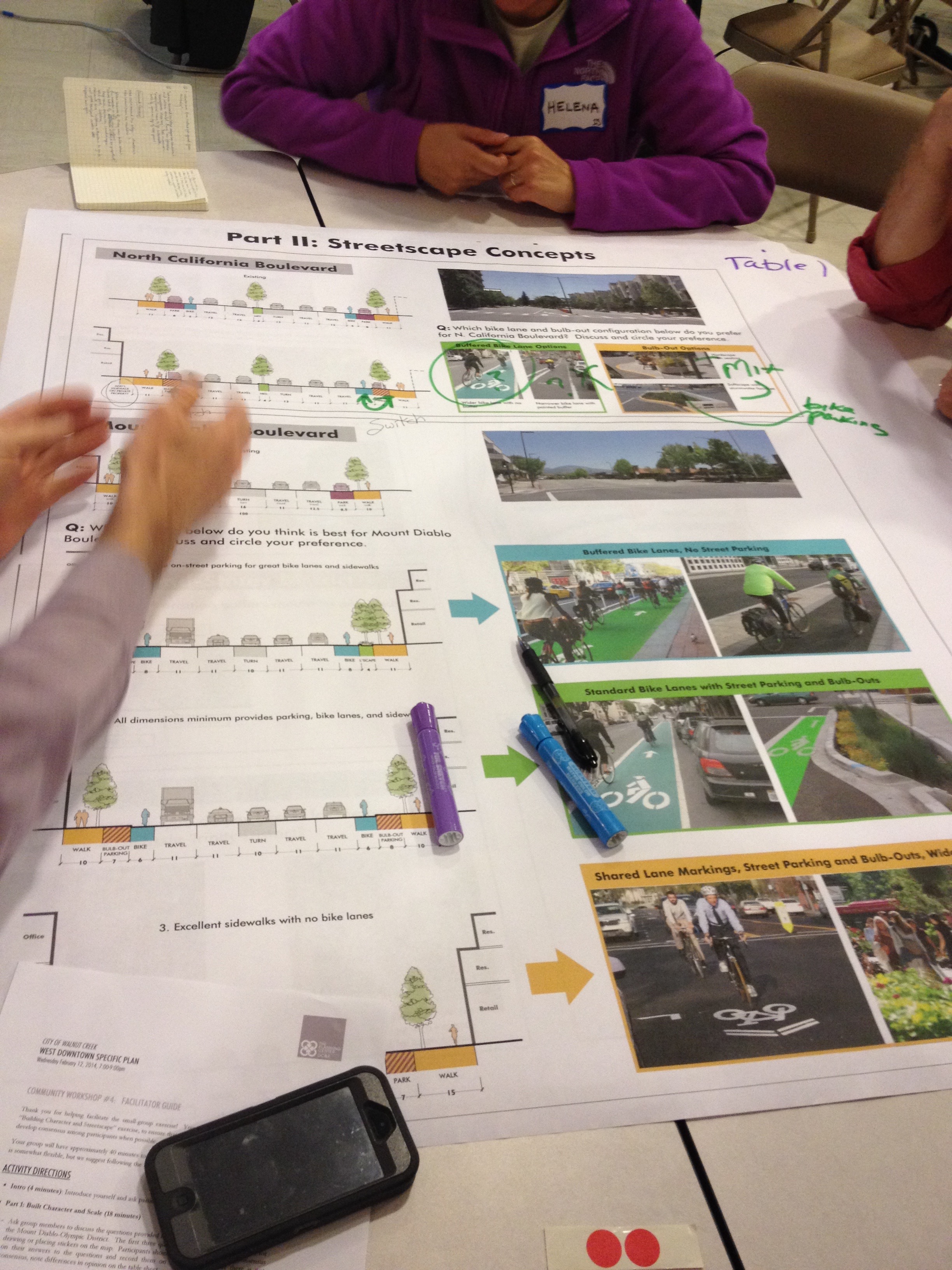

City and county planners are engaging productively to create measures to meet the goals of the regional Sustainable Communities Strategies (SCSs) under California’s Senate Bill 375 (“Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act”- Steinberg 2008), but more staff and technical assistance, particularly for financing mechanisms, is needed. Infill housing is necessary to reduce commute distances and regional vehicle miles traveled. Yet, bike and pedestrian infrastructure is communities’ highest priority for retrofitting existing neighborhoods. In places where cooperation among jurisdictions exists, particularly with leadership from multicity agencies, multifamily housing is shown to be a higher priority than in places where this cooperation is not present. This suggests a need for finding ways to promote cooperation between cities on SB 375 implementation. One way that this is already happening is through multicity organizations such as county transportation authorities and councils of governments that represent multiple cities and towns within a county. Recommendations include increasing capacity and technical assistance for such partnerships, while expanding funding and incentives for compact development in urban areas and suburbs.

Student Research

This report provides a historical context for the Sustainable Communities Initiative in the San Francisco Bay Area by examining efforts from previous planning eras, as represented by three key documents: the Bay Vision 2020 plan (1991); the Smart Growth Strategy/Regional Livability Footprint (2002); and, most recently, Plan Bay Area (2013). The report examines how all three plans treated the Initiative report’s key areas of emphasis: incorporating equity considerations, creating a process that is inclusive of all stakeholders, and achieving sustainable post-grant implementation of objectives.

The Bay Area’s governments’ and public agencies’ embrace of regional planning, along with their approach to questions of equity and sustainable implementation, have been evolving. For decades, the region has struggled to accommodate increased growth while maintaining the integrity and sustainability of its natural environment. In the mid-20th Century, two agencies—the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC)—emerged from a tangle of public and private stakeholders to become the dominant actors in the region’s current regional planning efforts. Their effectiveness has been hampered by their extremely limited authority over land-use decisions and tensions between themselves and local jurisdictions that resist regional authority.

From a starting point in the mid-20th Century, when they were not a priority for early regional planning efforts, the prominence and role of equity and inclusion have evolved. Between 1999 and 2008, the concept of equity was still largely viewed as an outcome of the process. By the time of Plan Bay Area in 2013, it had taken on a larger, more visible profile, with a broadly adopted position that acknowledged inequality up front and attempted to incorporate diverse needs within a community as part of the process, rather than as an outcome.

The planning efforts in the first two eras (the Bay Vision 2020 plan of 1991 and the Smart Growth Strategy/Regional Livability Footprint of 2002) focused entirely on increasing access to economic opportunity and reducing local pollution. Plan Bay Area (in 2013) differed from those predecessors by using metrics that emphasized affordability of housing and transportation in order to evaluate whether the benefits and burdens of Plan Bay Area were shared equitably among all residents in real-world measures. As an effort to institutionalize these goals in a sustainable fashion, Plan Bay Area incorporated an Equity Analysis Report supplement and integrated these metrics into the scenario performance analysis to help select the preferred scenarios. Under Plan Bay Area, the lead regional planning agencies have made progress toward being able to tie financial incentives to actual implementation of plans—a shift from where this narrative starts in the mid-20th Century.

This dissertation examines the local and regional politics of state-mandated sustainability planning using a survey and case studies of regions in California post-Senate Bill 375 (“Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act”- Steinberg 2008). Data collection included interviews with local and regional actors in the Bay Area and the Los Angeles region on multiscalar cooperation, as well as a survey of local planning directors in four regions (Sacramento, Bay Area, Los Angeles, and San Diego) on local political and capacity constraints on implementation. It finds unevenness in the local implementation of the law’s Sustainable Communities Strategies (SCSs) within and across regions, but also greater-than-anticipated levels of cooperation between cities and county-level agencies. A variety of interpretations of sustainability and a broad range of incentives are at work in local planning efforts to achieve regional emission reductions. Suburban and rural areas face different challenges but enjoy opportunities for reducing vehicle emissions that are potentially large. Much of the implementation work in these areas during the first round of SCSs gave rise to local experimentation and built upon an existing patchwork of climate planning. County level agencies play an underexplored role in shaping and supporting these local responses to state and regional incentives for sustainability planning.